Diamonds might not be forever. Is Botswana prepared?

Prices of natural diamonds are sliding as lab-grown diamonds take a growing market share. What impact is this having on Botswana and what can the government do to adjust to this new reality?

Botswana is the world’s second largest diamond producer after Russia. It also has the disadvantageous position of being the most mineral-dependent country in the world. Mineral products account for a staggering 92 percent of Botswana’s total exports, with diamonds alone making up 80 percent of its total exports. Diamonds account for one third of the government’s fiscal revenues and one quarter of GDP.

Diamonds are a tricky mineral to be so dependent on and, with prices in decline, Botswana is facing economic turbulence. What can we expect in coming years?

The contrived value of diamonds

Diamonds are unlike most other minerals in that their value generally does not derive from their properties (except for their limited industrial use) and demand for them is not driven by increased manufacturing, construction, or other economic activities. Whereas copper is valued for its high thermal and electrical conductivity and chromium is highly resistant to corrosion, a diamond’s value is more artificial: it is valuable only because we believe it to be so. We see diamonds as status symbols, and this drives a self-perpetuating demand for them: we buy them because they’re valuable, and they’re valuable because we buy them.

Our belief that diamonds are valuable was created in large part by De Beers, the world’s biggest diamond company. They did this by influencing both the supply and demand of diamonds. By the 1950s, the company controlled around 80 percent of the global market share. They wanted to sell more diamonds and so sought to create demand for them beyond industrial use. This led them to launch their famous ‘A Diamond is Forever’ ad campaign, cementing an association between diamonds and engagement rings and the durability of diamonds and life-long commitment.

De Beers’ significant market share gave them market power - they were able to control global supply and also had an incentive to do so: by ensuring that demand always exceeded supply, they kept diamond prices high. Although diamonds are not actually that rare, they were made to be precious through De Beers’ cartel-like control over supply and, although De Beers’ control of the market has waned since then, the perceived value of diamonds has endured.

Strategic benefit sharing and wealth management

Over time, the Government of Botswana negotiated strategic arrangements to secure a more favourable share of diamond wealth. The Government of Botswana established a 50-50 joint venture mining company with De Beers, Debswana, which operates most of Botswana’s diamond mines. The Government of Botswana also purchased a 15 percent stake in De Beers itself. The deal between De Beers and the Government of Botswana has gradually been improved in Botswana’s favour over time, with the government now receiving 80.8 percent of Debswana’s profits. The government is also entitled to sell 30 percent of Debswana’s diamonds (rising to 40 percent in 2030), but this is less important in financial terms than the profits it receives from Debswana.*

High reliance on mineral exports frequently causes macroeconomic and fiscal challenges for a country, but Botswana has historically navigated this risk relatively well thanks to prudent fiscal management. Diamond revenues have been spent on investment in human and physical capital, with significant improvements in health, education, and public infrastructure testifying to progress in this regard. Fiscal management was also assisted by a sovereign wealth fund, the Pula Fund, which was established in 1993. The Pula Fund is designed to accumulate balance of payment surpluses for investment in foreign assets, thereby keeping these earnings out of the small domestic economy (which would otherwise face currency appreciation) while yielding returns for the future. It was also designed to act as a stabilisation fund to smooth government spending over time by saving surplus revenues during boom periods that can be drawn down during low-price periods, thereby protecting against cuts to public services during downturns.

What’s happening with diamond prices?

As with other minerals, diamond prices have fluctuated over time. But waxing and waning demand for diamonds is less tied to economic activities themselves and more reflective of periods of prosperity. The figure below shows an index of diamond prices over the last 15 years, with fluctuations tracking global events. Prices collapsed as demand evaporated in the wake of the 2008 global recession, then grew to a peak in early 2012 on the back of growing demand from China and India as per capita income in those countries surged. Prices reached another low point in 2020 amid the Covid-19 pandemic, which interrupted supply chains and postponed many engagements and weddings. Immediately post-Covid, demand surged again, reflecting a spate of rescheduled weddings. Once the wedding backlog was cleared, prices declined again but didn’t stabilise where they had been pre-Covid - they’ve continued to slide.

What is driving this lower demand for diamonds and is demand likely to recover? The economic downturn in China has notably affected demand, with some indications that demand in China has dropped by up to 50 percent. Consumer preferences are also changing, with young people prioritising sustainability and ethical sourcing. The biggest impact, though, has come from the entry of lab-grown diamonds into the market. Unfortunately for Botswana, diamonds are one of the very few commodities that can be synthetically engineered, with lab-grown diamonds being chemically and physically identical to natural diamonds but costing significantly less. Additionally, the United States is a major export market for Botswana’s diamonds and Trump’s 37 percent tariff on Botswana’s exports will further dampen demand.

While economic growth may rebound both in China and globally, and Trump’s tariffs will hopefully fall away, consumer preferences are less likely to shift back towards natural diamonds when a cheaper option exists that many see as more environmentally and socially sustainable. What we’re seeing may not be temporary dip in demand, but a more lasting structural change.

The potentially permanent nature of lower demand for natural diamonds spells huge trouble for De Beers and the Government of Botswana. Diamond sales were down 40 percent in 2024 and Debswana had cut production at its mines by 31 percent by late 2024 and appears to be making a further 16 percent reduction in 2025. De Beers has been stockpiling diamonds due to supply outstripping demand - it had a $2 billion stockpile at the start of 2024 that it hadn’t been able to shift it by end of the year. De Beers’ parent company, Anglo American, has announced that it is looking to sell its 85 percent stake in De Beers as part of broader strategic restructuring. Amid this dire situation, the government continued to bullishly demand more favourable terms from De Beers.

The Government of Botswana’s response to its changing prospects

Botswana has historically been lauded for its prudent fiscal management of diamond revenues. However, something appears to have changed in recent years, evidenced by a notable rise in government spending even as diamond earnings have declined. Much of this increased spending is recurrent or consumption spending rather than investments.

Government of Botswana spending**

Source: Author’s construct using data from Botswana’s Ministry of Finance budget documents

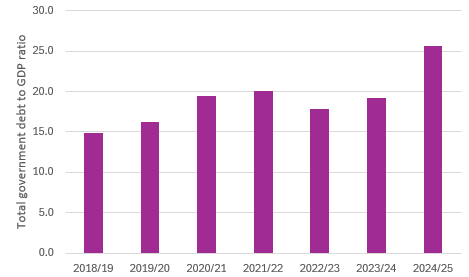

This increase in government spending has been funded by growing debt, with government debt as a share of GDP increasing from 19.2 percent in 2023/24 to 25.5 percent in 2024/25. This is a very risky trajectory given the high future uncertainty in the diamond market.

Botswana government debt to GDP**

Source: Author’s construct using data from Botswana’s Ministry of Finance economic and finance statistics

The Government of Botswana has not been on course to adjust to the country’s changed reality. But things may still be turned around in time. The October 2024 elections saw the ouster of the Botswana Democratic Party, which had ruled the country since its independence in 1966. Duma Boko and his left-leaning Umbrella for Democratic Change won the election and stronger management of the country was almost immediately visible. A new agreement between the Government of Botswana and De Beers was soon signed, including a 10-year sales agreement and a 25-year extension for Debswana’s mining licenses. Importantly, the new government’s 2025 budget looks to begin to curb the budget deficit left by the previous government.

There’s much hard work ahead for Duma Boko’s administration. Getting Botswana’s prudent fiscal management back to what it once was is a key priority. Botswana’s new vice president and finance minister, Ndaba Gaolathe, has acknowledged that Botswana’s famed fiscal discipline has eroded in recent years, with political interference having seeped into the country’s economic management. Turning this around and getting economic stability back on track will be key to preserving Botswana’s status as an attractive investment location. This will attract more diverse foreign investment and aid efforts to progressively advance economic diversification in the country. Where possible, further development of labour-intensive sectors, such as tourism, call centres, and business process outsourcing services, should be prioritised to help address Botswana’s burgeoning unemployment problem, with unemployment reaching 34 percent among young people.

The natural diamond industry will persist for some time still and continuing to get as much broader value out of diamond mining as possible remains important. This includes further strengthening upstream and downstream linkages, promoting local participation in supplying mining companies with goods and services and ensuring that a larger share of diamond cutting and polishing takes place domestically. It will also be essential to work with De Beers to sustain the value proposition of natural diamonds through marketing that appeals to younger consumers. This could include sharing more traceability information to alleviate fears of conflict origins. Marketing campaigns could also emphasise the important economic benefits that the purchase of natural diamonds brings to producing countries such as Botswana. Linking purchases of Botswana’s diamonds more directly to funding education, healthcare, and infrastructure development in the country could go a long way to retaining loyalty to Botswana’s natural diamonds.

* Edits have been made here to include the Government of Botswana’s share of Debswana profits and to note that this is more important in financial terms than the government’s share of diamond sales.

** These figures have been updated since initial publication of this piece to reflect figures constructed by the author using data directly from Botswana’s Ministry of Finance. Government expenditure information is taken from Table V. Government debt and GDP figures are taken from Quarterly Debt Updates.

If you enjoyed this post and are keen to read about other African mining and energy developments, please subscribe!

I’d also welcome your thoughts on this issue - please feel free to engage in the comments section below.